3 day-old baby boy in Dibana village, Maharastra, India.

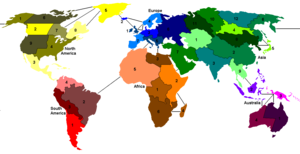

As part of the group, Mom Bloggers for Social Good, we are working on spreading information about the State of the World’s Mothers report, and their annual report about the best and worst places to be a mother. The State of the World’s Mothers (SOWM) report is Save the Children’s signature annual publication, which compiles global statistics on the health of mothers and children, and uses them to produce rankings of nations within three groupings corresponding to varying levels of economic development. They have produced the reports annually since the year 2000. Though the core report indices are the same every year, each year there is a new feature or story angle added to it. In 2013, the new feature is the Birth Day Risk Index — the index compares first-day death rates for babies in 186 countries to identify the safest and most dangerous places to be born.

Watch video of the project here, with Jennifer Garner, Jennifer Connelly, and Alyson Hannigan and moms from around the world:

http://youtu.be/aVUQ5yK5R0k

The United States has the highest number of first day deaths of babies of any industrialized nation; nearly 11,300 babies die here every year. American mothers may be surprised to hear this, as we think our healthcare is superior to mothers in sub-Saharan Africa, southeast Asia, and other areas with high infant mortality rates. Save the Children’s annual report recommends several actions to solve this problem, such as addressing the underlying causes of infant mortality, increasing health care workers, investing in low-cost, low-tech health care solutions, strengthening health care systems and increasing access, and increasing committments and funding to saving the lives of mothers and children.

In a show of support for Save the Children, American bloggers are sharing their own birth stories. I am more grateful than ever to have experienced the miracle of not only bringing two healthy children into the world, but also the glory of experiencing motherhood for the last seventeen years. Birth wasn’t easy, but the payoff has been magnificent:

my first baby

“Jennifer. Stop. Look at me. Look at me. You must stop pushing right now.”

My brain and body scrambled to focus on her blue eyes. Something wasn’t right. This wasn’t happening the way the book said it would. What is she saying?

I had watched all the movies, attended the birthing class, packed my bag, bought the diapers, and laid out your little white sleeper, recently laundered in Burt’s Bees baby soap, ready to bring you home.

“Stop,” her voice repeated. “This is important.” My midwife’s normally calm demeanor was punctuated with urgency.

I couldn’t pry my eyes open. The pain was overwhelming; no time for medication, this was happening old-school style. My breath came in gasps, my fear in waves.

I searched for my husband, his hands on my legs. Finally he came into view, his blue eyes holding it all in.

“Her cord. It’s wrapped around her neck. You need to stop so I can flip her out. You must not push-do you hear me? “ I snapped into focus. I inhaled and for a moment, granted her request.

My body and brain were operating with broken connections, like a static dead space. I gave up control out of sheer and utter terror that my baby would be born dead.

This wasn’t the way it was supposed to happen.

No one says that first babies come early. Tales of endless labor, walks around the hospital and enduring hours and hours of waiting for her to come were all I’d been told. Nothing-nothing at all had prepared me for these 30 minutes of laying in the hospital bed, feeling her force her way into the world.

The seconds felt like hours. I naively tried to regain control; not realizing that from this point on, you would shape every thought, every action, and every moment of my life.

“Jennifer, when I say so, you need to push harder than ever before. Go deep inside. Growl like a mama bear, and do it with all your power. Do you understand?”

Obediently, I complied.

One. Two. Three.

But wait – this isn’t how it is supposed to be. I haven’t even gotten into the birthing chair. The nursery-the laundry hasn’t been put away into your little dresser. We haven’t even decided on your name yet… I don’t know where you are, or what to do. The only thing I do know is that I’m not ready for this. Am I really going to be somebody’s mom?

But there you were, somersaulting into the world, slightly violet, but breathing. And alive.

And absolutely perfect.

The struggle was over. We made it. Nothing in life could ever be harder than that, I imagined. I held you to my chest and breathed you in, feeling your warm stickiness. I clasped your tiny fingers.

“What is it?” I heard my mother hesitantly, yet pleadingly, call from behind the closed door.

“It’s a girl,” I panted in reply.

And forever afterwards, life as I knew it ended and began at precisely the same instant.

Few hours old twin babies are seen at Pailarkandi union, Baniachang district of Habiganj in Bangladesh. The twins’ mother has had four antenatal visits to the clinic and the babies are full term and a healthy weight. Every hour, 11 babies die in Bangladesh their lives cut short before theyre even four weeks old. One in 19 children under five dies needlessly of diseases we know how to treat or prevent. In some regions the figures are even higher: in Baniachong and Ajmiriganj, where Save the Children is working, one baby dies every day, meaning tragically that many women there have lost at least one child. In one village currently without a clinic, locals told us that 9 out of 10 women that live there lose a baby. Most of these children die because they dont have access to even the most basic healthcare. For every 10 births in Bangladesh, 8 mothers have to give birth in their home on a dirt floor without a skilled health worker present putting the life of their baby at risk. Only 37% of Bangladeshi children with suspected pneumonia have access to a health worker and only 22% of those receive antibiotics for it. This treatment gap has often tragic consequences. The lack of good food plays a devastating role, too. Nearly one in four Bangladeshi babies is born underweight, and the damage from malnutrition often lasts a lifetime. Horrifyingly, nearly half of the children in Bangladesh suffer irreparable damage to their bodies and minds a condition known as stunting all because they cant get the nutritious food they need to grow and develop. 5% of the worlds children affected by this condition live in Bangladesh.

This post was inspired by the novel A Constellation of Vital Phenomena by Anthony Marra. In a war torn Chechnya, a young fatherless girl, a family friend, and a hardened doctor struggle with love and loss. Join From Left to Write on May 20 as we discuss Anthony Marra’s debut novel. As a member, I received a copy of the book for review purposes. To purchase your own copy, visit http://amzn.to/XWBaxN.

This post was inspired by the novel A Constellation of Vital Phenomena by Anthony Marra. In a war torn Chechnya, a young fatherless girl, a family friend, and a hardened doctor struggle with love and loss. Join From Left to Write on May 20 as we discuss Anthony Marra’s debut novel. As a member, I received a copy of the book for review purposes. To purchase your own copy, visit http://amzn.to/XWBaxN.